Water Cooler Small Talk, Ep 5: What Does Having a High IQ Even Mean?

A thorough and intuitive explanation of the deeply misunderstood intelligence classification for both humans and AI

Ever heard a co-worker confidently declaring something like “The longer I lose at roulette, the closer I am to winning?”. Or had a boss that demanded you to not overcomplicate things and provide “just one number”, ignoring your attempts to explain why such a number doesn’t exist? Maybe you’ve even shared birthdays with a colleague, and everyone in office commented on what a bizarre cosmic coincidence it must be.

These moments are typical examples of water cooler small talk — a special kind of small talk, thriving around break rooms, coffee machines, and of course, water coolers. It is where employees share all kinds of corporate gossip, myths, and legends, inaccurate scientific opinions, outrageous personal anecdotes, or outright lies. Anything goes. So, in my Water Cooler Small Talk posts, I discuss strange and usually scientifically invalid opinions I have overheard in the office, and explore what’s really going on.

🍨DataCream is a newsletter offering data-driven articles and perspectives on data, tech, AI, and ML. If you are interested in these topics subscribe here.

Here’s the water cooler moment of today’s post:

- I undertook an IQ test, and the results showed that I’m in the top 5% of the smartest people in the world. Actually, what is the average IQ?

- The average IQ is 100.

- No way. That can’t be right — 100 is too low!

At this point, I have to confess, I was also a little confused myself — I didn’t have a very clear idea of what IQ really measures either, but the math of this seem a little suspicious, don’t they? A score of 100 seems almost too average, right?

So, what’s happening?🤔

While IQ tests are rigorous and quantitative, it is difficult to define what exactly they measure, as intelligence by definition is a rather abstract concept. In any case, unlike other clearly measurable things, as for instance one’s mass or height, there’s really no universally accepted definition for what qualifies as intelligence. Thus, it is kind of hard to measure something that we don’t have a robust definition for. In fact, IQ tests are one of the most common cases where statistics are misused. The confusion emerges from several misconceptions about how IQ scores are calculated, what they supposedly measure and ultimately what they mean.

🧠 What about the IQ scale?

An intelligence quotient (IQ) is a score calculated based on standardized tests aiming to assess intelligence. There’s a really long list of different types of standardized tests, focusing on any imaginable area of intelligence, like spatial reasoning, verbal comprehension, working memory, processing speed, logical deduction, creativity, mathematical or practical problem-solving. In any case, the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS) or the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, are some of the most widely administered and respected IQ tests. Other not so commonly used IQ tests include Raven’s Progressive Matrices or Cattell Culture Fair Test. Different IQ tests emphasize on different cognitive skills, thus, it only makes sense to compare results of the same test, rather some IQ test.

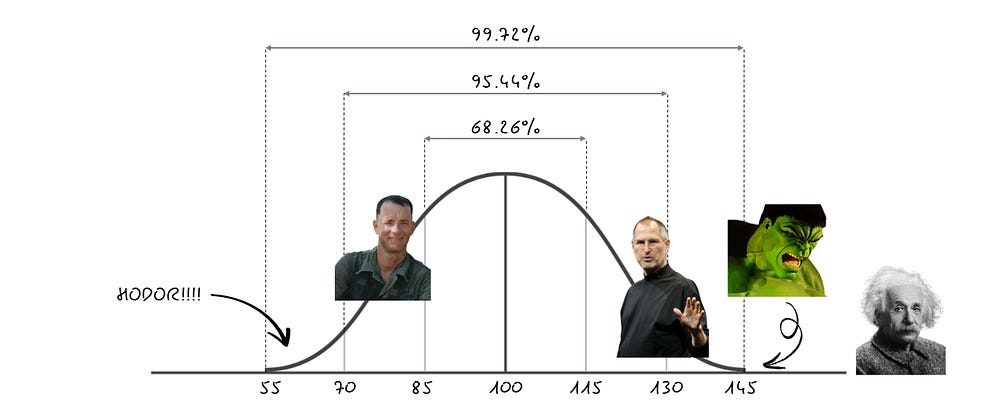

But, here’s the sauce: IQ scores are not fixed values, but rather they’re statistically normalized to follow a specific Bell curve, with a mean equal to 100 and a standard deviation of 15. This means that by design:

The average score is set to be 100.

Most people (about 68%) score within one standard deviation (±15 points) of the mean score, meaning their IQ scores fall between 85 and 115.

Scores above 130 or below 70 represent roughly the top and bottom 2.5% of the distribution, respectively.

So:

Being in the top 5% isn’t really that brilliant, since you fall within two standard deviations of the mean. IQ 130 is often the threshold for identifying giftedness in schools, indicating students that excel in STEM or creative writing. Highly successful professionals in fields like engineering, law, medicine or academia, performing tasks that require problem-solving skills, strategic thinking, and advanced knowledge will most probably have an IQ around 130.

100 can’t really be high or low by itself — it rather means that someone scoring 100 on the IQ scale, has a similar IQ with most people. By definition, the average adult having IQ 100 is able to manage daily life, maintain employment, and solve moderately complex problems. Depending on our cultural and societal views on how smart or not most people are, an IQ score of 100 can be respectively interpreted as high or low.

Nevertheless, IQ scores kind of fail to incorporate the dimension of time and the respective evolution of intelligence over time. Most probably a person with IQ 110 today is much more intelligent — whatever this might mean — than a person with IQ 110 in 1950s, due to the much more complex environment they live in. However, the IQ classification fails to incorporate this additional information. In other words, an IQ score represents one’s relative cognitive ability in comparison to their contemporaries, but doesn’t allow comparison between different time periods.

Irrespectively of the IQ scores failing to incorporate this info, people actually do perform better on IQ tests overtime — something also known as the Flynn Effect. In particular, the average IQ score has been rising by about 3 points per decade since the early 20th century. This means that someone with an IQ of 110 today would likely have had an IQ closer to 100 + (3 points per decade x 7 decades) = 131, if measured against the average population of the 1950s. This, doesn’t necessarily happen due to an increase in innate intelligence, but rather due to environmental changes. Over time, people get better education, have access to improved nutrition and health care, and ultimately a greater exposure to abstract reasoning tasks, driven by the rapid growth of technology and the complexity of modern world.

Interestingly, up until the mid-20th century there was also a different calculation method for IQ, nowadays referred to as ratio IQ. More specifically, ratio IQ was calculated as a ratio of one’s mental age over their chronological age, multiplied by 100. For instance, a 10-year old child who performs at the level of an average 14-year-old would have a mental age of 14. Thus, their ratio IQ would be 14/10 x 100 = 140. On the contrary, a child performing their age would by definition have IQ equal to 100. Anyhow, as you may have imagined already, this approach is problematic when trying to evaluate the performance of adults, as cognitive development does not progress linearly throughout life — what is the expected mental age of a 40-year old? How is it different from the expected mental age of a 45-year old? 🤷♀️ Modern IQ tests utilizing the normal distribution solve this problem and allow comparisons among individuals of different age groups.

Apart from controversies surrounding the IQ methodology and its inherent ambiguity, IQ classification also faces harsh criticism for encompassing cultural and linguistic biases. Those biases stem from the design of the test tasks, which frequently incorporate concepts, language, or problem-solving methods that are more familiar to some groups than others. In this way, IQ tests may fail to record the diverse ways intelligence manifests across populations.

Those cultural and linguistic biases that are incorporated in IQ tests have been historically used to justify discriminatory policies in immigration, education, and employment. For instance, the Ellis Island employed intelligence testing in the early 20th century to evaluate the the mental capabilities of immigrants, concluding that most immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe were not that bright. Similarly, in education IQ tests often result to the exclusion of students originating from minorities and marginalized groups from higher advanced academic opportunities. A striking example of this — the Larry P. v. Riles case — , underlines the discriminatory impact of IQ tests. Likewise, using IQ tests as a screening tool in employment may favor candidates coming from privileged backgrounds.

Ultimately, by privileging certain groups while marginalizing others, the misuse of IQ tests perpetuates stereotypes and systemic inequalities, and raises serious ethical concerns.

🤖 Oh look, it’s half-past AI O’clock!

But what about AI? Undeniably, ChatGPT and other advanced AI systems seem incredibly smart, don’t they? I wonder what ChatGPT’s IQ might be… As AI becomes increasingly integrated into our lives, we face new challenges in defining and measuring intelligence — not just for humans, but also for machines.

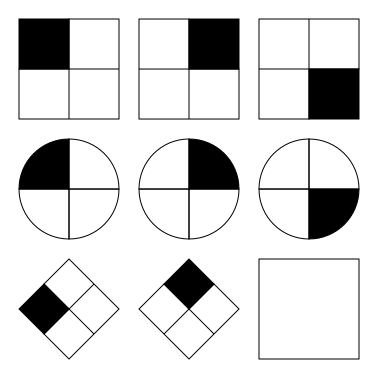

If you’ve ever taken an IQ test, or even a GMAT-type test, you already know that you can practice and learn how to perform good in such tests. If you solve a bunch of tests in advance, you will most probably improve your performance. The same applies to AI models — they are trained extensively on patterns, logic, and problem-solving tasks, which align perfectly with the design of many IQ tests. By repeatedly encountering similar problems, AI systems refine their ability to recognize and solve a portion of IQ test type tasks with remarkable efficiency. For instance, AI systems often outperform humans in solving Raven’s Progressive Matrices.

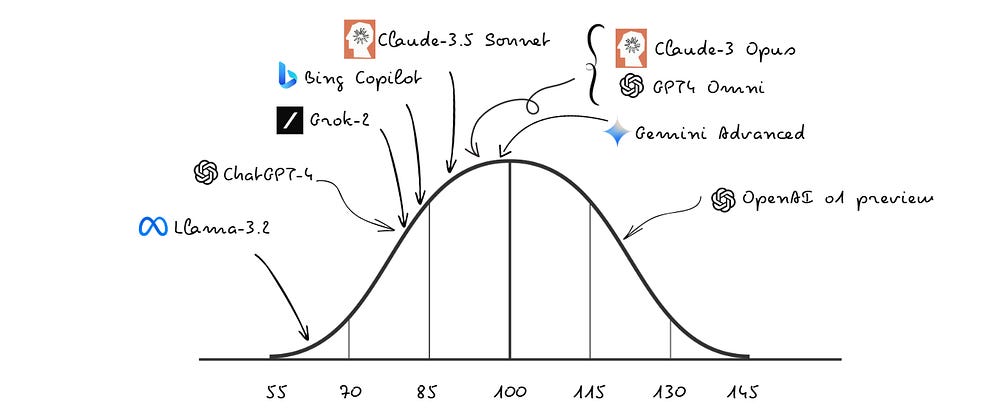

A very interesting project, namely Tracking AI, tracks the scores achieved by various AI models in the Mensa Norway IQ test. In recent evaluations, OpenAI’s o1 model achieved a notable IQ score of 120 on this test, correctly answering 25 out of 35 questions. This places the model above approximately 91% of the human population, indicating a significant advancement in AI reasoning capabilities. When evaluated on an offline test, the score of o1 falls to 98, nonetheless, remains superior to any other AI model.

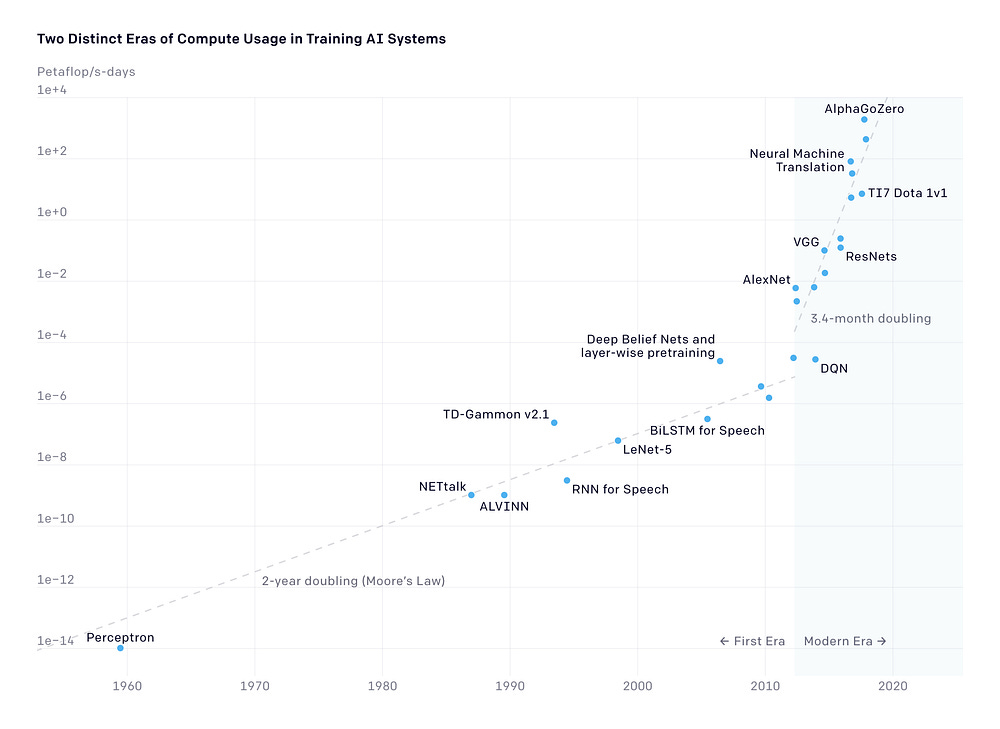

Similarly to the average human IQ rising over time due to the Flynn effect, AI performance also experiences an exponential growth, deriving from richer datasets, more powerful algorithms, and faster computational resources. Up until 2010, the improvements in AI power and performance aligned with Moore’s law, meaning that the compute usage doubled approximately every two years. Nevertheless, after 2010 there is a dramatic acceleration, with compute usage doubling approximately every 3.4 months. Essentially, AI computing power growth is exceeding Moore’s law, due to other factors apart the number of transistors on microchips, as for instance availability of training data and advancements in machine learning algorithms.

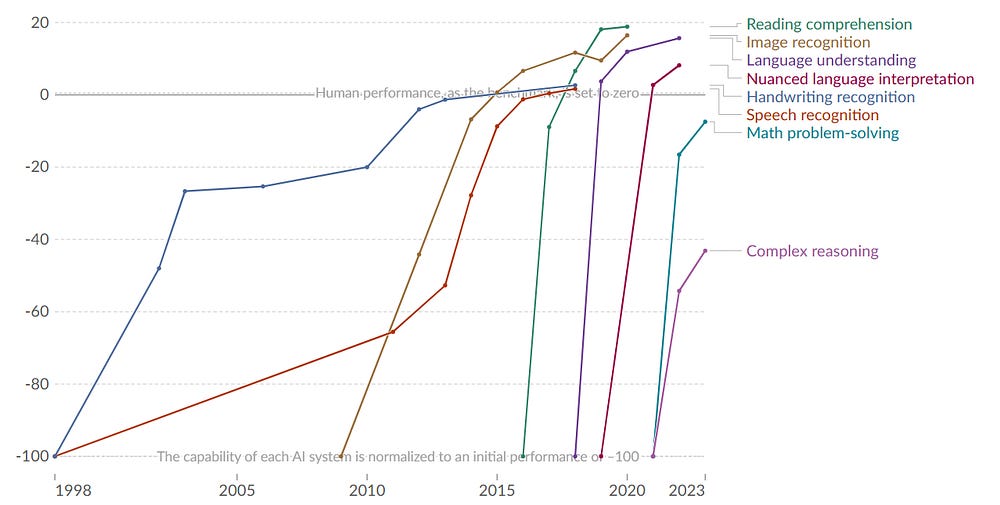

There are lots of metrics designed specifically to evaluate the “intelligence” of specific types of AI models, as for instance GLUE, SuperGLUE and SQuAD for NLP, or ImageNet, COCO and MNIST for computer vision. Nonetheless, most of these metrics focus on specific tasks, which most of the time AI models can perform extremely good in comparison to the average human. The rapid growth of AI performance over the last decade, has resulted in AI models outperforming humans in a wide variety of tasks, as for instance handwriting and speech recognition. However, for more complex tasks like mathematical problem solving and complex reasoning, human performance remains superior.

In his 2019 paper, ‘On the Measure of Intelligence’, François Chollet introduces the ARC-AGI (Abstraction and Reasoning Corpus for AGI) benchmark. This paper offers a transformative perspective on how we measure intelligence in both humans and machines, expressing the core idea that skill is not intelligence. In other words, tests — either for humans or machines — that focus on performance and skill in specific tasks or games, are not an adequate measure for intelligence. On the contrary, intelligence can be defined as the ability to learn and succeed on new, diverse and unpredictable problems. As explained on the paper, solely measuring skill at any given task falls short for measuring intelligence, because skill is heavily modulated by prior knowledge and experience — both for humans and machines.

More specifically, the ARC-AGI benchmark comprises of 1,000 logic puzzles, divided into training and testing tasks. Each puzzle includes two or more solved examples as part of the training set, and the goal is to recognize the underlying pattern, in order to solve a similar puzzle. LLM models may be able to produce coherent results for the simpler quizzes of the ARC-AGI dataset, but when the tasks progressively start to become more complex, LLMs don’t perform well.

A 2021 study reveals that an average person can successfully solve approximately 84% of the tasks in the public training set of the ARC-AGI benchmark. Naturally, a good score for an AI model in order to be considered on the right path to Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) would be above 84%. However, the achieved scores remain far lower:

the highest recorded score is 55.5%, achieved by MindsAI

OpenAI’s o1 model scores a surprising 21.2%

Ultimately, it is important to always keep in mind that AI is able to perform fairly good in traditional IQ tests, not because it is thinking, but because it has been trained to identify and apply similar patterns repeatedly, over and over again. LLMs may perform fairly well on traditional IQ tests, assessing verbal reasoning or arithmetic, but struggle with more sophisticated and complex tasks like those in ARC-AGI. Unlike traditional tests, ARC-AGI requires capabilities far beyond pattern recognition, as for instance abstract reasoning, generalization, or spatial and visual reasoning.

💫On my mind

In the words of Edwin Boring “Intelligence is what intelligence tests measure”. This famous quote highlights the inherent challenge in defining and quantifying intelligence — deciding on what qualifies as intelligence, and finding an appropriate way to measure it. Ultimately, intelligence is a subjective and multidimensional concept. What we choose to measure, and how we measure it, reflects our definition of intelligence rather than capturing its entirety.

We are fairly inclined to interpreting intelligence through a quantitative lens, usually associating with logical reasoning, problem-solving, mathematics, or verbal comprehension. This, largely happens because those aspects of intelligence are easier to measure — a phenomenon also known as the McNamara fallacy. However, those strictly measurable aspects are a rather narrow slice of all the elements our intelligence truly encompasses, as for instance creativity, interpersonal skills, empathy, adaptability or out-of-the-box thinking.

At the end of the day, intelligence is a construct. How we choose to define it and measure it is not just a scientific endeavor but also a philosophical one. In any case, a single measurement or test cannot encapsulate the full spectrum of intelligence. Whether human or artificial, intelligence manifests in countless forms, each valuable in its own.

Loved this post? Got an interesting data or AI project? Let’s be friends!

Join me on 💌 Medium 💼 LinkedIn ☕ Buy me a coffee!